“Hope springs eternal in the human breast;

Man never Is, but always To be blest.

The soul, uneasy, and confin’d from home,

Rests and expatiates in a life to come.” ― Alexander Pope, An Essay on Man, 1732.

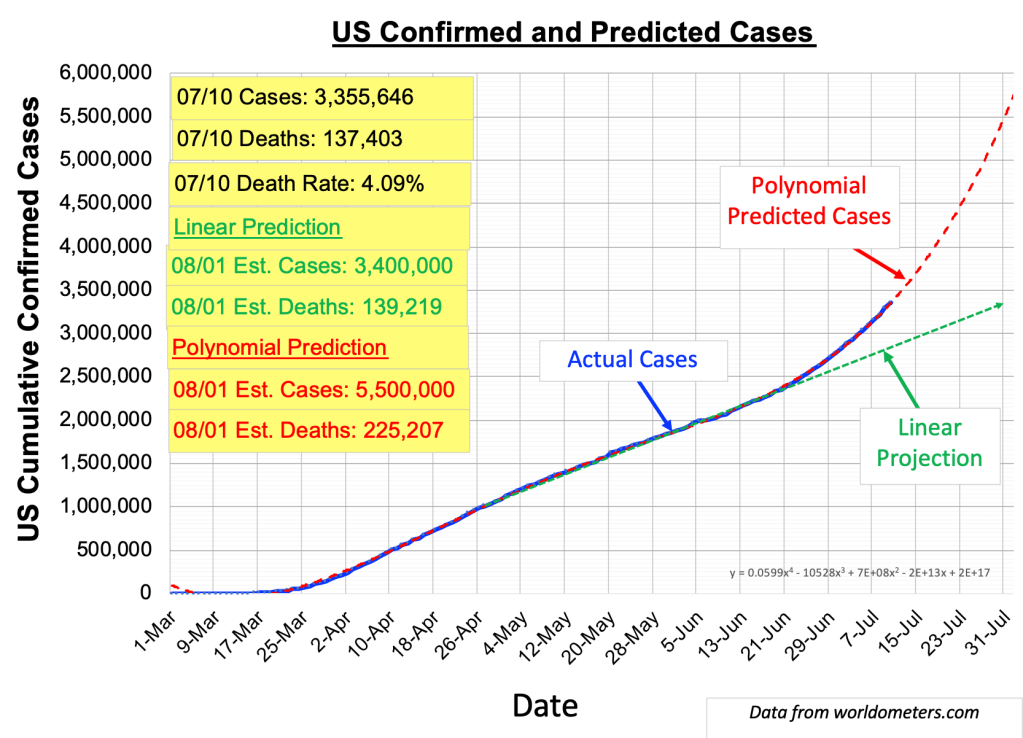

Note: After reviewing my previous post “Wait” I have come to realize that it may have tended somewhat, how shall I say, toward the apocalyptic. “You think? You had to include Titanic AND Hiroshima?” Fine, fine. I was trying to make a point. Which still stands. This whole pandemic thing is real and will explode over the next few months (see red-dashed curve below) – and to top it off is most likely return in Fall/Winter with its evil twin, seasonal flu. Yeah. I know, I know. Still very doomy gloomy. Sorry. To paraphrase Galileo’s whisper as he was placed under house arrest for the heretical notion that the earth circled the sun — Eppur si muove [“and yet it moves”].

So … given that Galileo was ultimately proven right, I got to thinking about how our situation might look – sometime in the future. Sometimes bad times — wars, plagues — lead to great advances in science, technology, and culture.

But first, the data:

Green-dashed curve good. Red-dashed curve bad. Really bad. And sad. We are back in exponential growth territory, where we when all this started in March. While we could discuss all the reasons for this dire situation, let’s leave that to Dr. Fauci and the vast unavoidable array of doctors and epidemiologists (and, sigh, politicians) who bombard us daily. For our purposes the data is what the data is. The red-dashed trend curve above projects a total of 5,500,000 cases by August 1. This is greater than projections from IHME and other sophisticated university and government models.

My curve is much simpler, but does match the data. I can only assume that the difference is due to the other models assuming some significant change in behavior or treatment in July. We will have to wait and see whose projections prevail. The number of deaths predicted above (225,207) is also much higher than that predicted by university models, which project about 150,000 deaths. I computed this by simply multiplying 5,500,000 by the current death rate of 4.09%. This may be overly simplistic, as the death rate is very likely to change (decrease or increase or both!) from now until August 1, which may be more accurately included in university models. I expect that my number will prove to overly large. Again, we’ll have to wait and see. … Now, speaking of the future, let’s find out how Oscar is doing there …

#####

Hope Springs Eternal

“Back in those days we didn’t know how it would all turn out.”

“I don’t remember anything about it. I was too little I guess.”

“You were about three years old.”

“Yeah. Well, Prof assigned us to write something about family history. I picked the Great Pandemic of 2020 and it said that would be fine.

“I still can’t get used to you calling your teacher ‘it’. Way back in the twentieth century we had actual teachers. People. You know?”

“I know, Grandpa. You always talk about Dr. Franklin.”

“She was one of my favorites. Smart. Really smart. And nice. Changed my life.”

“Prof is smart. Maybe he’s nice.”

“That’s another thing. We didn’t have “Profs” until we were in college.”

“College?”

“After grade school and high school.”

“Yeah, I don’t know what that means.”

“Well, the Pandemic changed things.”

“Why?”

“AI. Google. Do you know what 7 x 9 is?”

“An app?”

“No. How much it equals?”

“No. How much?”

“63.”

“How do you know?”

“I had to learn my multiplication tables.”

“Oh. I just ask Prof. Watch: Prof, what is 313 x 4555?”

“Wait, Oscar, not now. I thought you had an assignment.”

“Right,” Oscar says, “Nevermind,” blinking twice.

“Aren’t you going to take notes?”

Oscar smiles and points to his glasses.

“Right. No video, though, okay?”

“You want video? We can do that if…”

“No, no. Audio is fine.”

“Audio only.”

“So, you don’t remember anything?”

“I don’t think so. Maybe Starbucks was closed? I don ‘t know.”

“And now you’re thirteen.”

“Fourteen.”

“Fourteen, right. Just checking.”

Oscar blushes. “But you were there Grandpa. What was it like?”

“Oh. It was sad. Very sad.”

“The holos,” Oscar points again to his glasses, “show mostly statistics visualizations and vids of labs and lines of people with masks and stuff.”

“Right. But statistics don’t really tell the story. It started out small. A few people here. A few there.”

“And then everyone got sick.”

“Not everyone. And not right away. But way more than ever needed to.”

“How many?”

“Well, I think if you study those statistics you’ll see that over a million people died in this country. Not so in Europe. They handled the whole situation much differently.”

Oscar stares at me, mouth open. “A million people?”

“Mostly adults. Not a lot of little kids.”

“And not you.”

“Nope. We stayed inside mostly.”

“For how long?

“Almost two years.”

“Two years? That’s crazy! How did you ever even do that? Wow. That’s crazy!”

“We did go out from time to time, but when we did we always wore a mask, and even then your mom and dad wouldn’t let use see you for a few weeks after, just in case we caught it.”

“But you didn’t catch it.”

“Nope. But lots of people did.”

“Why? They didn’t wear masks, or what?”

“There were a lot of reasons. Some people had to work so they had no choice but to go out, some didn’t believe it was all that dangerous, some thought masks were weird, and some thought they were tough enough, or young enough, or just didn’t like being told what to do.”

“A million people got sick?”

“A million people died. Way more than a million got sick. Over two hundred million in the end, I think. Ask your eyeglass gadget there.”

“Two hundred million? How is that even possible?”

“Well, herd immunity – ask your ‘Prof’ there – happened once about two thirds of the population got it. There were about 330 million people in our country back then, as I recall.”

“Wow! Where did everyone live… that’s a lot of people. We don’t have anywhere near that many now. I mean…”

Oscar hesitates, gnawing his lower lip.

After a moment he says, “I bet the roads were a big mess, too. I mean, didn’t everyone drive in those days?”

“Sure did.”

“To go to work, or shop and stuff, right? Did you go somewhere to work?”

“I went to an office, yes, before the pandemic.”

“Really? What was that like?”

“Other than all the traffic getting there and back? It was nice in that it was easier to make friends and communicate with my fellow workers than it is now, when no one goes ‘in to work’ as they say.”

“And schools were like that too, right? Rooms with desks and real live teachers and everything. And real books, too.”

“Yes, real live teachers. Like Dr. Franklin.”

“I don’t think Prof is alive – I mean not that kind of alive. He sounds real and all but he’s really not, I guess. But he knows everything. I mean everything.”

“I see. And he wants a report.”

Oscar searches my face for signs of senility.

“When is it due?” I ask.

“Tomorrow.”

“Of course it is. What else would you like to know?

“What about vaccines? Wasn’t there a vaccine or something?”

“Oh, sure. But it didn’t come along for a few years. Early in ’22, I think. Something like that.”

“Why did it take so long? We just had Covid-31 and it only took a week. Everyone is fine. I got my shot yesterday. Weird, getting a shot by a hummingbird drone. They just flit around and don’t leave you alone until you give in. Sort of annoying, right Grandpa? You didn’t have that in those days, right?”

“No. Just old fashion shots. From doctors. We had to go in to get one.”

“Prof is a doctor. He does most things by studying my signals, but can’t do surgery or anything unless you go into the Center. Remember? For your heart?”

“I do remember.” Surgery by robot. Nursing by some sort of android’ish contraption. No Dr. Franklin. No Florence Nightingale.”

“Florence Nightingale? I wondered why they call the hummingbirds nightingales. Ha.”

“We learned a lot in those days, Oscar. They worked like crazy to hurry up. A couple of years to get a vaccine for a new virus was a miracle. It usually took many years.”

“Still…”

“They had a pretty good vaccine, as it turns out, in early ’21, but no one would take it.”

“Why not?”

“People were scared. It hadn’t been proven safe, and it was only about 65% effective. And then there were the crazies who wouldn’t get vaccinated no matter what.”

“What?”

“Sometimes it’s just easier to get an idea in your head or believe some convenient mumbo jumbo than it is to try and understand a little science. To think. You know? Luckily there were enough people back in the mid-twentieth century who were smart enough and willing enough to accept polio and smallpox vaccines — or who knows where we’d be.”

“Yeah. I got shots when I was little. From a real nurse once, too. I remember. But the Covid-19 vaccine. You got it, right?”

“Yes. In ’22.”

“Wait. Not in ’21? But you just said… Wait, you’re a scientist. Why didn’t you get it when it came out?”

“I wasn’t convinced it was safe. I studied the scientific papers and wasn’t persuaded by the research or data that it was safe. There was a lot of political pressure for everyone to take it. In the end some people who did get it got sick. Maybe 20%. Some died.”

“Wow. So you waited another year?”

“Almost a year, yes. But we wanted to see you grow up. So we stayed safe, and waited.”

Oscar touches his chin, mimicking one of my mannerisms.

“And here you are, on the cusp of manhood!”

“Grandpa!” Oscar groans, blushing.

“So we stayed inside while the rest of the country – or most of it – just sort of gave up.”

“Gave up?”

“That’s how we got to herd immunity. Everyone just sort of went back to “normal” and accepted that people will die. In the end the fatality rate was about half a percent. With 200 million or so eventually infected you get about a million deaths by late ’22.”

“So people just… died?”

“It was very bad. Horrible, actually. After a while the hospitals couldn’t handle it and doctors and nurses got sick sooner or later, exhausted, PTSD, like they had been in battle. Amazing people. Never saw anything like it. I still hold them in awe. Eventually they set up tents and arenas and things like that to hold all the patients. Things got better as they figured out better care, but the National Guard still had to come in to help, and all the big cities needed big refrigerated trucks for the patients who died. It was especially bad in late ’20, when the regular flu added to the mess. Pretty soon there were too many people to even have separate funerals so, well, they did the best they could.”

“You mean Mount Hope.”

We lock eyes.

“Yes.”

“Prof says there are thousands of people buried out there. Thousands.”

“It got to be hopeless to have individual graves. Everyone got upset at first, of course, but eventually just accepted it. So sad. So, so sad. There are Mount Hopes all around the country, mostly near big cities. Ask your professor there about them.”

“And no one did anything? I mean, to stop it? I mean, do like you did – stay inside and everything?”

“Not really. Everyone wanted to get back to normal.”

Oscar studies his fingers for a long moment.

“It doesn’t sound normal to me.”

“Oscar, Oscar, Oscar … when did you get so smart?”

Oscar closes his eyes, his face soft now.

“And that’s where…”

“Yes, she’s there. And her brothers. We did our best, but … the virus still found a way, somehow.”

“I’m so sorry Grandpa.”

“I know. I know, Oscar. But we’ve got you. Hope springs eternal.”

“I’ve heard you say that a million times.”

“What else can we say? What else can we believe?”

Oscar again goes silent, brow scrunched, staring at nothing.

I can’t help but love him, so hopeful. I sigh.

A long moment later his face lights up.”

“Dinner’s ready!”

“What? How do you know? We’re nowhere near the kitchen.”

“Grandpa…” Oscar laughs, touching his glasses. “Chef just configured it. My favorite!”

Personal Acknowledgement: The title of this post is in tribute to my dear Uncle Donald, a learned philosopher/historian/humorist who would often close a conversation with “Hope Springs Eternal,” which seems most appropriate and consoling in these uncertain times.